Roots & Routes

Heise, Ursula K. Sense of Place and Sense of Planet. The Environmental Imagination of the Global. Oxford University Press, 2008.

Modern environmentalisms have cultivated our sense of place. But the challenges ahead also require connecting this to a new sense of belonging – a sense of planet. This is how I read the central argument of Ursula Heise’s ‘Sense of Place and Sense of Planet. The Environmental Imagination of the Global’ (2008).

Heise develops a cultural theory for addressing the effects of globalisation, the imaging technologies which are its tools, and elaborates on risk theory. The outcome of these are to give directions towards what she labels as “eco-cosmopolitanism”. Eco-cosmopolitanism is environmentalism gone virtual, where wireless fibre is as much part of the fabric of nature as the air breathed where in your immediate locality. It is about allowing us to sense risk at different scales, from local to global, and to share that risk.

Risk theory, developed by Ulrich Beck (1992), is by Heise given more cultural and environmental connotations by referring to works on the human condition in emerging risk society. Of these I found Christa Wolf’s ‘Störfall’ and Gabriele Wohmann’s ‘Der Flötenton’ discussion of the Chernobyl meltdown in 1986 as interesting for exploring experiences and mixtures of risk, place and daily routines.

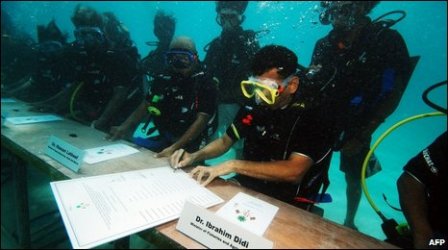

Taken together, Heise’s readings exemplify how globalisation exposes people to new types of risk, making it apparent that connections in our lives stretch far beyond the immediate concerns of the locale. Chemicals travel downstream; Chernobyl fallout drift across national borders; CO2 emissions changes climate everywhere (p. 150). What is the sense of place of the Maldives when its islands have been submerged under rising sea-levels?

Environmentalism is then, Heise argues, not one but several strands of thought, and has from its emergence in the 1960 been concerned with different types of risks. Most of its proponents have sought to uphold and protect the local against global forces imposing change, or deterritorialisation, upon it. Although many environmentalists have relied on imaging technology, like ‘Earthrise’ 1968 or ‘Blue Marble’ 1972, for rationale and sense of place, the movement have remained anti-technological.

Hostility towards deterritorialisation and technology is according to Heise misrepresentative of actual risks to environment and society. Risk is something that is formulated and adressed depending on what sense of place one have, or in the words of Simon Levin “the world looks very different, depending on the size of the window you are looking through” (p. 205).

When technology became digitized and data could be gathered from satellites and updated daily, the scales at which Earth was depicted made transition between global and local scales effortless, like in the software of Google Earth. Perhaps transcendence, or collapse, of scales is a better word than transition as this both implies:

- a user,

- a power relation,

But this is another topic than what Heise engages with.

The sources used by Heise relate not to technology itself but to the cultural employment of technology as an indicator of the emerging risk society. In the late 20th century, risk has shifted its emphasis from the local to the global scale. Of importance here is how cultural tropes shape the perception of previous risks when new, still larger, menaces may be of greater concern.

The dangers of nuclear disasters that reach across geographical, national, and social borders continue to reconfigure themselves in the cultural imagination, as the more recent image of an entire planet undergoing climate change superimposes itself on the older risk scenarios (p. 156).

Since new concerns shaped and reshape modern environmentalism, risk is a means for resituating place, relating it also to a sense of planet. Part of this involves harmonisising theories of sensing and belonging, like Heise’s, to the fieldwork (or activism) of environmental justice movements. It is by learning about the uneven effects of globalisation on communities and nature worldwide that new communities may be formed, and new meanings such as eco-cosmopolitanism, emerge. In this way, Heise sees globalisation not as a deterministic force for a risk society – but as enabler of new meanings, of risk sharing in the eco-cosmopolitan future.

Heise is clear about her assumptions: Communities are, in the words of Benedict Anderson, imagined (1983). And the sense of belonging, and risks, can be understood and read as cultural strategies of contemporary literature, like the appropriation of Chernobyl for weaving together daily life and risk in ‘Störnfall’ and ‘Der Flötenton’. Although these works support Heise’s theory and choice of sources to develop eco-cosmopolitanism, it would be interesting to see how “Sense of Place and Sense of Planet” for sake of argument could engage with historians like Oliver Zimmer (2003) whose critique of Anderson questions the ‘modernist’ idea of communities (e.g. nationalism) as imagined. Perhaps this is the topic for a future discussion (the next book!)?

What I find most provocative about Heise argument is the potential she sees in technology and globalisation. The cultural outcome of their development is still in the balance. Imaging technology are tools in the hands of users, or activists, who from their deterritorialised and destabilised nations may grow a new interconnected world. Roots, environmentalist sense of place, is useful for risks against local issues. But the risk society is a global world, where we must choose our routes, of what risks we are willing to share with others (p. 10, 147). That if your roots are cut, then choose your route all the more freely.

But one could stress more fervently that globalisation and technological development are not neutral instruments or by whom they are used. One such case is where national locality, and interests, control which patch of the internet you may use. Google Maps depict Krim as part of Ukraine vis-á-vis Russia depending on if your wi-fi connection is in Kiev, or Moscow. Who influences the imaging technologies we use for sensing the world? Technological literacy and ownership are also part of our sense of place and sense of planet.

In this way, roots are not cut but contaminated; while routes may restricted to recommended trips. Where Heise end with analysing the effects of globalisation and technology, we should complement by studying its causes – the chain of events preceding the uprooting of roots, and when routes first were trodden.

References

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso, London 1983.

Beck, Ulrich. Risk Society. Towards a New Modernity. Sage Publications, 1992.

Heise, Ursula K. Sense of Place and Sense of Planet. The Environmental Imagination of the Global. Oxford University Press, 2008.

Zimmer, Oliver. Nationalism in Europe, 1890-1940. Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.